Results 1,021 to 1,050 of 1480

-

2018-05-28, 11:36 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2007

- Location

- Bristol, UK

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

They dominated because they provided the largest and most stable element of the army. It's not a coincidence that little is written about everyone else involved, when you read the accounts from the Peloponnesian War. You could be forgiven for thinking the only fighting that took place was between hoplite phalanxes.

The rich chose to fight in the phalanx because that's where the generals were expected to be (in the front row, ideally). The best-equipped men were supposed to be at the front, it was part of their civic duty and showing their personal commitment to the state. Many of the more affluent men would be hunters, often on horseback, but they didn't fight that way.

Greece didn't have a meaningful archery tradition, but they did have one with javelins. There's plenty of evidence that hoplites usually went into battle with two spears - a lighter dual, role one that could be thrown and a doru, or else with a javelin and doru. Plenty of hunting with javelins from horseback, too.

The light infantry did "train" with their weapons in their lives, poor men (in rural areas) hunted to eat. Hunting is transferable to skirmishing in a lot of ways, though the javelin and sling were more traditional Greek hunting implements than the bow. They didn't have composite bows, they came from the east (though the Kretans had them, but it didn't seem to spread far from their island - their practises of banditry and piracy probably reinforced that adoption).

Note Athens was the exception when it came to mobilising their lowest orders as oarsmen. Most other states weren't willing to make the political concessions necessary in return for getting native rowers. Other states used professionals, ie mercenaries hired from particular communities (like the Cilicians), who often turned their hand to piracy when between employers.

Athenian oarsmen weren't professionals for the most part, though there will have been a certain number who did nothing else since they always kept a certain proportion of their navy active (though that varied hugely over time). Most were the same sort of militia as the hoplites, regular citizens who mobilised to defend the state.

Note those sieges are all overseas, not on the Greek mainland. They were the actions of the Delian League against people who didn't just come out and fight in the traditional way.

I don't think so. Again it was custom, while men trained in their free time - especially in the gymnasion - they wanted a decisive clash so everyone could go back to their farms. Just like the earlier Roman legionaries, fathers trained sons, uncles trained nephews, cousins trained cousins and so on. Then they'd gather on feast days to practise the martial dances in formation to remind them how to stand in a phalanx.

Most of the battles on the mainland didn't really need anyone else. There's no mention of light infantry or cavalry action, just the main clash. Maybe we could assume those elements were still involved, but they don't appear to have been decisive.

Hoplites didn't need to sail a ship, they were the marines for boarding actions (just over a dozen per ship for a trieres).

Thessaly was very different. It's a big open country by comparison to the rest of Greece, and developed it's own style of warfare as a result. The hoplite class never became as powerful there as it did further south, and they had to content with Makedonia on their border, too.

As for tyrants, they made use of mercenaries (Greek and otherwise) for their military needs. People loyal to them, not to the demos.Wushu Open Reloaded

Actual Play: The Shadow of the Sun (Acrozatarim's WFRP campaign) as Pawel Hals and Mass: the Effecting - Transcendence as Russell Ortiz.

Now running: Tyche's Favourites, a historical ACKS campaign set around Massalia 300BC.

In Sanity We Trust Productions - our podcasting site where you can hear our dulcet tones, updated almost every week.

-

2018-05-28, 02:59 PM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Thanks, that's what I figured. He's also pretty clearly describing wagons being used offensively which is cool. Though he does point that they required very flat ground and claims that it was a relatively uncommon tactic.

Defensive wagon forts of course never really went away. IIRC wagons mounted with volley guns or "arquebus a croc" swivel guns were still used defensively well into the 17th century.

I've seen illustrations like that before, though my impression was that the pavisers were more for defense rather than breaking up enemy pikemen. Given that the swiss and germans would have frequently encountered opponents using both pikemen and shieldbearers in the late 1400s but were still so successful, presumably Monte is still oversimplifying a bit here.

Something I've learned recently is that according to Spanish sources the "rotela"/"rodelo" was specifically an italian weapon and completely unknown to spain until the Italian Wars. Instead spanish infantry mustered in the 1490s broke down into crossbowman, gunner, "Lancero", and "Escuado"/paviser. (it seems that both had both spear and shield, but the paviser perhaps had a shorter spear and pavise while the lancer had a longer spear and a half-pavise/"medio pavés")

Salazar in his translation of The Art of War apparently went into more detail than Machiavelli's descriptions of la Barletta and Ravenna and claimed that the spanish shieldbearers there were actually armed with a type of pavise from northwestern iberia.

In 1503 both of these were officially replaced by pikemen and the spanish army technically never really had soldiers called "rodeleros". There are examples of individual spanish commanders in sicily or italy requesting some number of "rodelos", usually along with an equal number of partisans. So it might be that the original "rodeleros" were actually based on Italian spear and shield infantry like the ones shown in this illustration of Fornavo:

Last edited by rrgg; 2018-05-28 at 04:54 PM. Reason: fixed date

-

2018-05-28, 05:59 PM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jan 2014

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Did an essay on this a while back, let's see if I can remember my points.

So one of the most important things to remember about Greece is its geography. It's a load of mountains with relatively little proper flat land and what flat land there is is really rubbish for farming. This means three things, thing one is that Greek cities tend to be absurdly hard to take; it's quite easy to find a nice unapproachable hill to sit on top of if you're surrounded by hills. Thing two is that cavalry are absurdly expensive, as it's a pain to find enough land to keep horses. This means they're both a very small group and rather underdeveloped ('cause there's not many people messing around with horses to find interesting new ways to use them). Thing three is that if your crops get burnt they are very hard indeed to regrow, olive groves in particular take ages to come back.

What does this all mean? Well, if you so chose you could very easily retreat to your polis and wait the enemy out. However, if you do that they'll just take out all your crops, meaning you'll starve within a couple of years. Thus, you want to have the enemy in your lands for the absolute minimum time possible. The best way to do that is go out and meet them in a decisive battle, which they'll probably accept as they don't want to be drawn into a long, bloody and ultimately pointless siege either and they really don't want you getting behind them to go burn their lands. Now light infantry and cavalry are both great, but they generally rely on having lots of space to work in, as otherwise their mobility advantage is totally eroded. Unfortunately, if there's one thing Greece does not have, it's wide-open spaces. Thus, what you really want to do is pack as many heavy infantry as you can into the limited space of the pass and drive them into the enemy until one of you runs out of troops. Light infantry can do some work here, both skirmishing before the main clash and messing about on the flanks once battle is joined in earnest, but cavalry can't really to the same extent. They can skirmish before the battle (and from what I remember they carried javelins for exactly that purpose) but once it's properly started they can't really do much, as if they try to go up the mountains they'll likely fall off (no saddles, stirrups or anything of that nature) or break their absurdly expensive horses' legs. They can also pursue a fleeing enemy, and at least one author claims that's about all they're good for, though of course that would have been the Greek disdain for cavalry (seen as cowardly for being able to leg it more easily than the footsloggers) coming out.

There definitely were other types of battle, from what I remember a lot of the Peloponnesian Wars involved the Athenians holing up and watching the Spartans march around their lands, and light infantry could of course ambush and generally irritate a foe in the runup to a big battle, but the decisive heavy infantry battle appears to be what was expected and what they trained for. A decent book on the subject is Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece, I remember using it a lot.

-

2018-05-29, 12:20 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

There are several well-documented examples of war-wagon columns being used offensively, often to make envelopment movements, going back to the first Hussite Wars in the 1420s all the way into Russian battles against the Turks in the 17th Century.

Yes but as I said - mostly in Central or Eastern Europe. War wagons were somewhat famously blasted to pieces by field artillery in a few engagements in Italy and in the Low Countries (i.e. what you might call 'Western Europe') in the 16th Century and declined in use there as far as I know.Defensive wagon forts of course never really went away. IIRC wagons mounted with volley guns or "arquebus a croc" swivel guns were still used defensively well into the 17th century.

Well, offensive and defensive use often go together, like with the wagons. But I agree military theorists do tend to oversimplify in order to make reality fit better to their theories - which is one of the problems with relying on them as a source.I've seen illustrations like that before, though my impression was that the pavisers were more for defense rather than breaking up enemy pikemen. Given that the swiss and germans would have frequently encountered opponents using both pikemen and shieldbearers in the late 1400s but were still so successful, presumably Monte is still oversimplifying a bit here.

The Rodolero and the Rotella are two distinct things, but the former was created explicitly in conscious imitation of Roman Legions. They worked for a while, had their moment so to speak in the late 15th and early 16th Centuries, but adjustment to pike squares troop ratios and equipment seemed to 'correct' this opening they were using (in particular against the Swiss) and their moment kind of ended.Something I've learned recently is that according to Spanish sources the "rotela"/"rodelo" was specifically an italian weapon

...

So it might be that the original "rodeleros" were actually based on Italian spear and shield infantry

It's worth noting though that they had a lot of success as a troop type in the conquest of Meso America (it wasn't just smallpox that won the wars for the Spanish) and in places like the Philippines. The Rodolero seemed to be a good fit for the Conquistador's mission.

The Rotella, along with a variety of smaller laminated pavises which seem to have been developed somewhat organically in the 15th Century separate areas of Europe including Lithuania, Catalonia, and lower Saxony - was of a species of what you might call "bullet resistant" shields. Some rotella might be literally bullet proof.

The Ottomans may have actually been the first to start fielding fairly large (33" or more) tempered steel shields capable of stopping an arquebus ball some time in the late 15th Century. These were used in the front ranks of their Janissaries in a few key battles, originally just in sieges (such as at Rhodes in 1480) but then later as an open field weapon. The Venetians quickly got wind of this and adapted their mercenary armies in Dalmatia to use these weapons, which they started making in the famous Venetian Arsenal. I believe Venetian ally Mathias Corvinus may have also used some of these steel shields in the Hungarian Black Army though they more typically used small laminated wood and textile pavises which also seemed to have some bullet (and bow and crossbow) resistant properties and were being used by Czech mercenaries and Lithuanian and Cossack raiding parties for sure at least as far back as the 1430s, probably back into the late 14th Century.

So the Italians did use Rotella type shields with spears (and with other pole weapons like bills and partisans) both in battle and in small scale engagements like street fights between different factions in a town or between rival nobles and their entourages.

Marozzo even shows you how to fight with a partisan and a rotella, and how to fight against it, in one on one combat.

The specific thing of taking a lightly armored (i.e. textile armor and a steel hat) man with a rotella and an arming sword ( or cinquedea or falchion or cut-thrust or espada ropera or what have you), and deploying these guys either as skirmishers or in their own columns, was I believe a Spanish or Castilian invention which as I said had it's moment, and may have even been copied by some others, but seems to have come and gone in about a 20 year span.

GLast edited by Galloglaich; 2018-05-29 at 11:14 AM.

-

2018-05-29, 12:38 PM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jan 2012

-

2018-05-29, 01:20 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Dec 2010

- Location

- What's this planet again?

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

From the Italian HEMA practitioners I know, they mean a large round shield, with a handle and an arm strap when they say rotella.

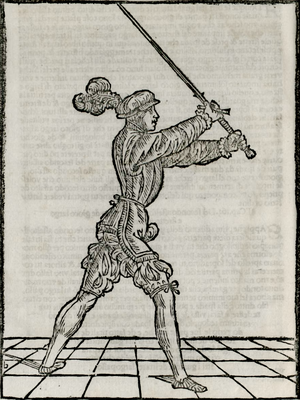

Here's an image from Capo Fero on the use of a rotella with what I think is a side sword. [Side swords are the transitional sword between the traditional cross-hilted one handed sword and the rapier]

And I've read somewhere that shield and swordsmen were dropped by the Spanish after it was decided they were too vulnerable to cavalry, despite their use against pikemen. For years I've thought they used a buckler as a shield, but no idea where I got the idea from. Although linguistically Rondelero is similar to Rondel, which makes me think of Rondel Daggers, which were medieval daggers used to fight in armour.

Also, we have shields in museums with a number of marks where they've been hit by gunfire. More than once, so it's less likely to be a proof mark, which makes me think there were effective shields to use against guns.

And weren't something like war wagons used by Americans crossing the great plains when fighting Indians? The impression I get is that they worked well up until the 20th century, providing the enemy doesn't have firepower that penetrates wood, such as artillery. I recall somewhere they were used in the English Civil War at times when artillery wasn't around.My extended signature.

Thanks to the wonderful Ceika for my signature.

I have Steam cards and other stuff! I am selling/trading them.

-

2018-05-29, 02:07 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Well, yes, essentially.

Personally based on the length I would call those rapiers rather than sideswords but the fine distinction is basically a modern one, in the period they would just refer to them as 'swords' usually (at least in the period literature) or sometimes 'dueling swords' (especially when cracking down on their use in legal rulings) or 'thrusting swords'.

We have the terms 'spada da lato' (sword of / on the side) from Italy and Espada Ropera (sword of the [civilian] robes) from Iberia (Castile / Aragon / Portugal etc.) which roughly correlate with a specific subtype of dueling or thrusting sword; a (usually) civilian weapon with a slightly shorter and wider blade with a little bit more cutting authority than a 'true' rapier. But there is a lot of gray area and overlap between a civilian 'sidesword', a similar but more robust military 'cut-thrust' sword, and a true rapier. Rapiers even had military variations vs. faster but flimsier pure dueling variants.

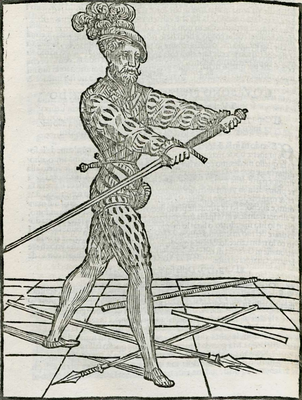

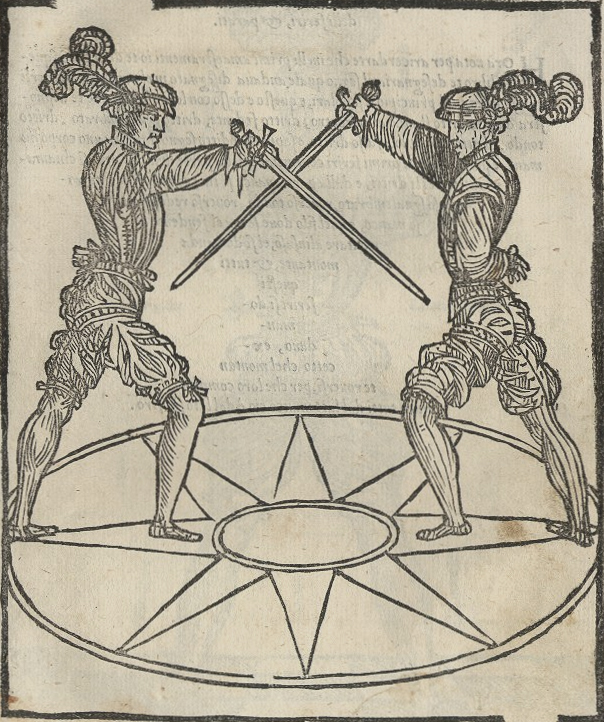

Most of the Italian fencing manuals from around 1500 onward have some kind of thrusting sword and also feature rotella; as well as longswords ("Spadone" or "Spada a due mani" when they are being specific) and sword and buckler, sword and dagger, two swords (aka "case of rapier"), sword and cloak, dagger alone, and some kind of spear, partisan or bill. Quite often pike and staff too. you will also see center grip bucklers, 'targets', something like 'mini pavises' and mazzo scudo and other types of shields.

As I mentioned upthread, here is Marozzo depicting Rotella with swords an with spear / partisan, as well as a wide variety of other weapons:

Spoiler: Marozzo training with different weapons

I think the rotella type shields fit on the forearm instead of the center grip because of the potential impact of a high-velocty missile like a bullet or a crossbow from a heavy military grade crossbow. Not to mention a lance or a Spadona.

In part, but they also lost their ability to penetrate pike squares when the latter increased the ratio of halberdiers and two handed swordsmen and re-established pikemen carrying longswords as sidearms. I don't think Rodolero has anything to do with roundel.And I've read somewhere that shield and swordsmen were dropped by the Spanish after it was decided they were too vulnerable to cavalry, despite their use against pikemen.

YepAlso, we have shields in museums with a number of marks where they've been hit by gunfire. More than once, so it's less likely to be a proof mark, which makes me think there were effective shields to use against guns.

I've never seen a cannon mounted on a wagon in North America though I think yes they would sometimes make a wagon circle and use them as cover against attacks by native Americans or bandits etc.And weren't something like war wagons used by Americans crossing the great plains when fighting Indians? The impression I get is that they worked well up until the 20th century, providing the enemy doesn't have firepower that penetrates wood, such as artillery. I recall somewhere they were used in the English Civil War at times when artillery wasn't around.

The most modern use of something like a war-wagon (which I've mention in previous incarnations of this thread) is the Tachanka, a wagon based machinegun system invented by the Ukranian anarchists "Black Army" in the Russian Civil War (and probably derived from old Cossack War Wagon traditions dating to the 15th Century)

Of course tanks and APCs also in some way derive from this idea, as do 'technicals' - trucks with heavy machine guns mounted on them used so widely now in war-zones in the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa.

G

-

2018-05-29, 03:16 PM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2017

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Ok, now I am confused. I thought targets and rotellas were the same kind of shield, and that targetiers was essentially the English term for rodeleros.

Are targets different? If they are, I am guessing they are centre-grip, like a large buckler? Thinking some more, are targets similar to the Scottish targe?

I appreciate that definitions were not reliably used at the time, but I have seen target/targetiers appear quite a lot.

-

2018-05-29, 04:13 PM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

My impression that the rodeleros were named after the rotella/rodela.

Are you sure that they began as a conscious imitation of the ancient roman legionaries? or was it more like the Swiss pikemen where later observers drew a lot of parallels with the ancient macedonians, but the Swiss and their tactics were still very different from how classical phalanxes were described?

The other popular explanation seems to be that the spanish preference for swords, shields, and darts was a holdover from their experiences fighting the moors. In particular the 1481-1492 Granada war which consisted almost entirely of sieges and guerilla fighting on mountainous terrain.

https://web.archive.org/web/20120307...ago/apprec.htm

This would seem to fit with the Spain's experiences in the Italian Wars: after their defeat at Seminara in 1495, the Gran Capitan switched to a fairly successful strategy of harassment and guerilla warfare while afterwords avoiding pitched battles with the French or Swiss whenever possible. This would also explain why Cortes brought so many sword and shield men with him to the americas.

According to the Tercios of Flanders blog, it was apparently Salazar who in 1536 suggested that tercios include 1/3rd rodeleros, and it's not clear if that ever went into practice. Instead for most of the later 16th century the rodela seems to have mainly been used by officers and some armored pikemen, who would hire a page to carry their shield around and give it to them for use in a skirmish or a siege.

http://ejercitodeflandes.blogspot.co...s%20defensivas

I agree that the main reason behind the rotella's popularity in skirmishes and battles was probably that it was better at resisting penetration from halberds, lances, and projectiles. In Monte's section on skirmishing he does mention that:

"A leather parma should not be placed too close to our person. For then any weapon would penetrate it and do us harm, if we do not carry other defence underneath, and one should not keep it far away, but at a medium distance and in a neutral place to respond to all parts."

---

On a somewhat related note, I was looking back through that Monte translation and his description of the "partisana" actually does sound a bit more like the ox-tongued spears in that fornovo illustration than it does like later partisans:

"A partisan (partisana), also called this in the vernacular, is a weapon combined with a staff, and is a little longer than the height a man can reach with his arm raised, of which the iron seems to be like the iron of an ancient broad sword. But the iron of the partisana is shorter, though it cuts more widely on both sides, and it has a point"

Monte's take on the partisan and rotella:

"

XXX. ON PLAY OF A SWORD WITH ROTELLA, WHICH IS LIKE A PELTA, EXCEPT THAT IT IS LARGE AND WHOLLY MADE OF WOOD AND A HANDLE. BUT THE PLACE WHERE WE SHOULD HOLD IT IS DIFFERENT FROM THE PELTA, AS IT CONTAINS TWO HANDLES, LIKE A PARMA, AND THE ARM ENTERS THROUGH ONE, TO LET THE HAND TAKE HOLD OF THE OTHER. AND THE ROTELLA IS NAMED FROM ITS PROPERTY OF ROUNDNESS.

When holding a sword and a rotella, one should follow the same blows as if we play with a leather parma, in the way we have said above, and for this it should have handles, like a parma has, that is, one close to the other, by which we take hold of the rotella, since in the way in which it is used, the arm is placed very much inside in the handles. And then it is a great hindrance for us, when it cannot be moved fast and cover the whole person, and also the rotella remains so close to us that, although it passes a little forwards, the adversary’s sword reaches our head or another limb.

"

XXXIV. ON THE WAY OF PLAYING WITH PARTISAN AND ROTELLA. A PARTISAN WE CALL A HAFTED WEAPON SOMEWHAT LONGER THAN A POLEAXE, WHICH HAS A BROAD IRON LIKE AN ANCIENT SWORD, THOUGH WIDER AND SHORTER.

In play of partisan and rotella we must walk above ourselves, until it is possible to see what the adversary wants. And at that time we should do the play of the poleaxe, entering and recovering moderately and often, threatening the face with a short blow. Then we should send forward a long blow to to the lower parts, the hand running along the shaft or, as we would say, rolling the partisan under the hand, throwing at the other’s legs. And we should always parry whatever blows the others can deliver, turning aside head and legs, as we do with the poleaxe, and in parrying we must contrapassare or go on the side, throwing one blow above and the other below. He whoever knows how to cover himself with rotella and sword will be easily covered in an equal way if he has a partisan, especially if he knows the play with the poleaxe. And in this there is indeed not too much need of a rotella, except when the adversary would force the partisan outside the hand against us, remaining very close, and then there would perhaps not be time to parry it. Positioning ourselves around the adversary, if he has a high partisan and goes ahead of the rotella too much, we must meet the point of his partisan with our rotella to make him enter into the rotella. And when he sets about pulling it away, some adversity can happen to him. Therefore we should take precautions, so that our point does not contact the other’s rotella through the coming together

"

XXXV. ON TWO PARTISANS WITH A ROTELLA.

When holding two partisans with a rotella, one should throw one of them, remaining at a medium distance from the adversary, and as soon as it reaches, we must arrive with the other held with both hands, to strike the adversary in another place, which he leaves uncovered, since he rolls around to turn aside our partisan, and in the meantime he remains impeded and uncovered, and even though he does not turn around, he is to some extent impeded, since he is holding the partisan by the middle and with only one hand, and we are holding ours with both hands by the calx. Therefore, before he can guard himself, he is running into the greatest danger. And this blow is principal in the partisan, or whenever we are holding one weapon for throwing and another for keeping in our hand. If the other throws his partisan against us, it is fitting to contrapassare to the side, turning his blow aside. And the rotella should reach under our right armpit and remain fixed there, and immediately we must carefully withdraw a little. For if it happens that the enemy holds his partisan with both hands, we have an opportunity to parry ourselves.

"

-

2018-05-29, 04:23 PM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

The exact definitions were never really consistent and could change quite a bit from author to author. Usually rondel or target to the English in the 16th century referred to a shield worn strapped to the forearm, between 1-3 feet in diameter, and made of either leather, wood, or metal.

-

2018-05-29, 04:32 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

I think they are overlapping terms, my understanding is 'target' is a broader and more general term than rotella or rodela. It typically just meant a medium sized shield sometimes round but sometimes of different shapes, whereas a rotella was a round shaped, steel, (usually tempered steel) shield larger than a buckler but smaller than a pavise.

As a general rule late medieval and Early Modern technical terminology tended to be more flexible than modern, not necessarily because they were sloppy in their thinking or imprecise. Sometimes that was the reason. But often particularly in the Renaissance or late medieval period it's just because they were more accustomed to and comfortable with the notion that all things have multiple meanings, even contradictory ones, and also multiple interpretations and names. This is in part due to using multiple languages. An educated person might read and write in 2 or 3 vernacular dialects, and a regional trade language or two, plus at least some Latin.

When discussing technical matters they were also used to quoting many different Auctores (acknowledged Authorities or "Experts") from widely different eras, religions and cultures. Pagan and Christian Greeks, pagan and Christian Romans, Moors, Jews, Arabs and Persians, and early and late Latinized European scholars from dozens of different places across several Centuries (some anonymous or known pseudonyms) were all considered qualified experts on many subjects. One had to be good at juggling these various perspectives to make sense of the world especially in the 'hard sciences'.

I can't remember where I read the bit about Rodelero's being a Renaissance revival of Roman Legionairre (or their slightly odd version of it) I think Machiavelli mentions this and Piccolomini too but I can't remember chapter and verse.

GLast edited by Galloglaich; 2018-05-29 at 04:42 PM.

-

2018-05-29, 04:41 PM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2017

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Ok, thanks for clearing that one up folks :)

I didn't realise rodeleros were lightly armoured- my mental image of one is wearing half-plate...Last edited by Haighus; 2018-05-29 at 04:41 PM.

-

2018-05-29, 04:46 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

I'm sure there were variations as the practice did have it's moment and spread around a little.

But by my understanding, usually just textile armor (aside from a helmet). Maybe sometimes a cuirass.

Their role was basically as light infantry, a type of skirmisher, almost more like an ancient Peltast or Velites than a Legionaire, but the nuance was instead of a light wicker or leather / hide shield, they had that Rotella which could stop bullets and crossbow bolts, so they had a certain extra resistance to ranged attacks.

Probably equivalent though to dealing with the lower velocity but still lethal javelins, darts and sling stones of antiquity.

And with the sword and shield, they could be dangerous close-in.

Also as I think someone alluded, not that different in some respects to earlier medieval Iberian fighters like the Almogavars, (see Catalan Grand Company) and Iberian warriors going back to the era of the Roman conquest. These guys used javelins, including those exceptionally dangerous iron ones (soliferrum etc.) but when the enemy wavered, would also close in (yelling their terrifying slogans) and carve the enemy up with butcher knives and so forth.

GLast edited by Galloglaich; 2018-05-29 at 05:30 PM.

-

2018-05-29, 05:32 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2007

- Location

- Bristol, UK

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Just on this point, it goes back much earlier still than the Roman conquest. Possibly even before Carthaginian colonisation of Spain, though things get murky as to how much the natives adopted Carthaginian armaments, and how much were their own originating ways of fighting.

Though the notion that Iberians were only skirmishers comes from later Roman authors, by which time there was no longer any need for close order infantry. Before they'd conquered the place, Iberians were just as able to stand in the fighting line as Romans or anyone else.Wushu Open Reloaded

Actual Play: The Shadow of the Sun (Acrozatarim's WFRP campaign) as Pawel Hals and Mass: the Effecting - Transcendence as Russell Ortiz.

Now running: Tyche's Favourites, a historical ACKS campaign set around Massalia 300BC.

In Sanity We Trust Productions - our podcasting site where you can hear our dulcet tones, updated almost every week.

-

2018-05-29, 06:13 PM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Yeah, I agree that rotella seems to be a more specific term than target.

The other thing to keep in mind when it comes to terminology is that in many contexts the difference really didn't matter all that much. For instance when it comes to the bill and halberd you sometimes see even fencing treatises start out repeatedly using the phrase "bill or halberd" but then eventually switch to just "halberd" since both weapons were used in pretty much the exact same manner.

Targeteers could potentially be either light or heavy infantry. You had for example wealthy soldiers who could afford servants or draft animals to carry around really heavy armor and a pistol-proof shield for them, or you might have poorer soldiers carrying a shield of some sort because they couldn't afford better armor. For instance William Garrard in the 1580s recalled that some light armed pikemen "who amongst some nations for want of brest plates of Iron, vse tand lether, paper, platecoates, iackets, &c. For a gorget, thicke folded kerchefes a∣bout their neck, a scull of Iron for a head péece, and a Uenetian or lether Shéeld and Target at their backes, to vse with their short Swordes at the close of a battaile, and in a throng."

There are a number of examples in Montluc's memoirs where he describes himself or some other officer fighting with just a mail shirt, helmet, sword and target (and the targets back then apparently weren't bullet proof, a fact which nearly cost Montluc his left arm early in his career). Sir Roger Williams mentions that the spanish would sometimes during a siege send forward a small number of trusted officers or other soldiers armed with very heavy proofed armor and a very heavy proofed targets to inspect the enemy wall for breaches.

On the military theorist side William Garrard, Thomas Digges, and Fourquevaux all thought that it would be a smart idea to give all arquebusiers and even all armored pikemen a small, lightweight leather target on their backs which they could use with their sword in close combat when needed.

Overall it seems that regardless of the type of target carried, if a targeteer is expected to assault a breach or fight alongside pikemen in a close-quarters "throng" he ought to wear as much armor as possible. If he's expected to fight alongside skirmishers or climb up ladders or towers then lighter armor might be better, perhaps just a mail shirt.

-

2018-05-29, 06:32 PM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Something I've noticed before on Manuscript miniatures is that a lot of the illustrations from 1350-1450 seem to show a similar sort of infantry as Spain armed with a mix of large pavises and smaller round shields. Maybe the late medieval shift from shields to two-handed polearms was really more of an English/French/German thing for most of the 14th and 15th centuries?

http://manuscriptminiatures.com/sear...n=&manuscript=

-

2018-05-30, 03:07 AM (ISO 8601)Firbolg in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Kiero, thank you for your answers and congratulations on your knowledge -- it isn't just deep, it's also clearly built in a systematic way.

Originally Posted by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1955

Originally Posted by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1955

-

2018-05-30, 12:43 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2007

- Location

- Bristol, UK

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Wushu Open Reloaded

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Wushu Open Reloaded

Actual Play: The Shadow of the Sun (Acrozatarim's WFRP campaign) as Pawel Hals and Mass: the Effecting - Transcendence as Russell Ortiz.

Now running: Tyche's Favourites, a historical ACKS campaign set around Massalia 300BC.

In Sanity We Trust Productions - our podcasting site where you can hear our dulcet tones, updated almost every week.

-

2018-05-30, 01:29 PM (ISO 8601)Banned

- Join Date

- Mar 2018

- Location

- The Moral Low Ground

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

So in another forum I'm discussing medieval dyes.

I believe that there were plenty of common plants available to the lower class. At least Blue and Yellow appear to be easy to acquire for europeans.

The other dude insists blue was difficult to get (based on a source concerning paintings), and really seems to have exaggerated/extrapolated a bit too much from a few dyes being banned for class reasons.

Problem is, the dude waves around sources (I don't think he's great at using them) whilst I sorta just read a hundred not-well-referenced sites that seemed in general agreement. Would anyone know of pretty conclusive sources for the availability of dyes to the masses.

I guess this applies to the dyes armies wore, if it's not military enough.

-

2018-05-30, 03:27 PM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Does he think most medieval people just wore burlap sacks?

-

2018-05-30, 04:21 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

I'm sorry don't have any sources off hand, and I'm referring here to the high to late medieval period, but your friend is wrong, in my opinion.

By say the 1200's, most fabrics were imported already dyed from places where they made the textiles, just like today. People did fairly often tailor and sew their own clothing at least to an extent, though there were also tailors and people bought off the shelf clothing so to speak. We know this from many records, for example often part of somebodies pay was in textiles. There are many surviving laws and guild statutes dictating that apprentices have to be given so many yards of this or that type of cloth (often specifying the color, as different crafts wore different colors and patterns as a type of uniform) a couple of times per year to make clothes.

There was even by then such a thing as cheap homespun cloth, and even cheap homespun cloth that was undyed, but knights, mercenaries, mid-ranking burghers, and even relatively well off peasants could afford nice quality imported textiles for clothing, including dyes, which far exceeded what most of us wear today in terms of thread count, quality and of course natural fibers.

By the 1400's basic single-color kermes, madder red or woad blue homespun textiles like you might see worn by generic 'villagers' in a TV show or video game (what I call the 'pastel peasants' variant of the 'medieval cavemen' Trope) would be limited to only the most remote and poor rural areas, like way up in the mountains or deep in the woods somewhere. In a town in Latinized Europe, even servants were typically well dressed, as were the servants of nobles. The outfits of the servants reflected on their masters.

(I would post paintings but if your friend discounts the evidence of paintings then it's hard to prove the point... some people think the Earth is flat what can i say...)

Again, even servants clothing was typically far better than what most people wear today. Textiles of black, scarlet and purple (the most expensive colors), beautiful damask patterns, gold and pearl embroidery (as in real gold wire), fancy furs like mink, ermine and sable, and so on, were indeed so common that various Sumptuary laws were passed to try to ban commoners from wearing them. The efficacy of these laws can be judged by their serial repetition.

One of the reasons Landsknechts dressed so lavishly with so many layers of so many different colors and patterns (including slashing their overgarments so you could see the linings and undergarment colors) is because of their specific exemption from sumptuary laws. A lot of Landsknechts came from poor areas in Swabia like deep in the Black Forest where sumptuary laws were actually enforced, so it was liberating for them to strut around looking like a kaleidescope.

For sources, try google searches with terms like "textile dying flanders" or "textile dying Milan" or similar. Off hand the main Late Medieval textile centers were Lombardy or Tuscany: Milan, Brescia, Florence, Siena; Flanders: Bruges, Ypres, Ghent, Lille; or Germany: Cologne (Koln), Augsburg, Strasbourg, Nuremberg and Ulm. I do remember reading an article once about cochineal dye in Venice. Cochineal is a bright red dye derived from an insect found in Mexico, and there was a sudden craze for it in the early 16th Century after it was introduced from the New World. Venice, lacking easy access to the Atlantic had to scramble to find a source but they did, and IIRC within a few years they started breeding the bugs in Italy. They eventually kind of cornered the market.

Looks like this book gets into that whole story a bit.

You can also check out Matthias Schwarz "The First Book of Fashion" - try a google image search for that. He was an accountant from early 16th Century Augsburg who had paintings painted of himself every few months or so throughout his life, kind of like a medieval Instagram.

More broadly, think about the implications of the Silk Road. The vast amount of Silk brought into Europe across thousands of miles century after century gives you some idea of the purchasing power of European people, it wasn't just nobles buying all that. The pull was strong enough that Marco Polo and family (first among many other Italians) made their way all the way to China. And as soon as that route was cut off by the Ottomans, they found their way across the Ocean to find a new route... ;)

GLast edited by Galloglaich; 2018-05-30 at 04:23 PM.

-

2018-05-30, 04:21 PM (ISO 8601)Banned

- Join Date

- Mar 2018

- Location

- The Moral Low Ground

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

"Landknecht in medieval times had the authorisation to wear fancy and bright colors (normaly only reserved to nobility) to appear as an elite warrior troop (which was the case)."

Is some weird thing he's got in his head. I pointed out that banned dyes tended to be the expensive ones, not the bright ones, but the dude needs a source.

Also he had weird ideas about using leather to look wealthier/more elite, to which I responded with an argument about anyone elite and wealthy would use mail and nobody'd be fooled by leather, to which he pointed out that mail was heavy and... then I pointed out we were discussing an almost-corset over a gambeson, and mail's fine. He conceded but concluded that leather was easier on the legs than mail (dude was wearing trousers/gambeson) and... Well, I think he's a bit of a quack.

But I like debate so a source is a source...

-

2018-05-30, 06:13 PM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2017

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

I was under the impression that purple was basically unheard of in medieval Europe (outside of Byzantium), and had an almost legendary status as the colour of Emperors, due to the only available dye being Tyrian purple. Tyrian purple being famously expensive.

Also, I thought crimson/carmine could be produced prior to the introduction of cochineal from the Americas- cochineal is superb for producing the dye, but I thought there were closely related indigenous European species of beetle that could also be used to produce carmine. Presumably cochineal was far more effective and economical if this was the case.

-

2018-05-30, 06:22 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Maybe they mixed blue and red dye? ^^

Homebrew Stuff:- Lemmy's Custom Weapon Generation System! - (D&D 3.X and PF)

Not all heroes wield scimitars, falchions and longbows! (I'm quite proud of this one )

) - Lemmy's Homebrew Cauldron

You can find all my work here.

-

2018-05-30, 08:01 PM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2018

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Hello

I was lurking for quite some time and decided just yet to join the conversation. I must add that i really enjoy this thread and the deep knowledge of the people that post here.

So to the point. The great french historian Michel Pastoureau wrote a few books about the history of colors in medieval Europe. I read them some years ago so my memory may be foggy but to resume shortly: Blue was not really well considered during antiquity and the beginning of medieval time. It was effectively rare.

The promtion of the color took some time but the main change was between the XII and XIII century, what Pastoureau call the «*Blue Revolution*». I cannot remember exactly why (and a good friend borrowed the book)so i won’t risk a blunder but here is a serie of lectures from Pastoureau himself:

louvre.fr/les-couleurs-du-moyen-agemichel-pastoureau

(Sorry for the shabby link, i’m new here and have yet to prove myself to the power above)

The fifth is specificaly about Blue.

Obviously it is in French. And i just discovered it, looking for some sources. I will watch and come back with better informations as soon as possible.

So to be short blue was rare in early medieval time, albeit more for cultural reasons than availability ( but IIRC Blue is harder to fix than other colors).

-

2018-05-30, 11:40 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

-

2018-05-31, 12:35 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2012

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Bright blue dyes were rare. They were rare and expensive, made of crushed turquoise or similar semi-precious stones. During some periods bright blue was reserved for paintings of the Virgin Mary, for her mantle...

Blue dyes for clothes were kinda greyish and boring, hence the association of color blue and sadness...

I think french king Saint Louis was the first to popularize bright blue colour for clothes (maybe they dicovered cheaper dyes?)

-

2018-05-31, 12:43 AM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

-

2018-05-31, 03:53 AM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2017

-

2018-05-31, 04:15 AM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2018

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXV

Well not exactly. The King of France was important in his adoption. But it was Philippe Auguste and not Louis IX. And it seem that the better dyes followed in this case the growing symbolical importance of the Color and not the other way around like in XIXth Century with prussian blue and the american indigo.

The association between blue and sadness has more to do it seem with the romantics who made blue their favorite color (think of the blue vest of Werther from Goethe or the flower of Novalis.)

And the Color blue for the Virgin Mary is typically coming from the XII-XIII century.

So i have to speak about theology but i think it is art history here and not a religious topic... The XII century saw the «*theology of light*», a kind of new vision of the faith with emphasis on the lux, the divine light from above as opposed to the lumen, the light from terrestrial sources. The lumen was expressed with yellow or golden. But the lux saw the use of the blue more and more. So the Virgin Mary, Queen of Heaven, used more blue in her representations ( it should be noted that her liturgical color is white). To the point when it was the convention to use blue as her color.

Then came the King of France, who used blue in his coat of arms because the king of France does nothing like the others( and Philippe Auguste was the first, those who came before were king of the french.)

Saint Louis was important too, he seem to have liked the color and effectively his clothes were often blue but Philippe Auguste did it First.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

RSS Feeds:

RSS Feeds: