Results 601 to 630 of 1485

-

2017-10-20, 08:11 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Breechloading cannons were common in the 15th and early 16th century, but they were displaced by muzzleloaders. The designs probably couldn't keep up with the increasing pressures that solid cast muzzleloading guns could handle. That was the big development in cannons over the 16th century -- better metallurgy meant they could make guns that weighed less but still provided as much power.

I suspect that light swivel pieces didn't generate as high pressures, and maybe that's why more of them were breechloaders? (Certainly the stave built ones couldn't have handled high pressures, but the longer barreled Versos and Esmerils were cast).

-

2017-10-20, 08:17 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Well, I'm not sure if they really did become that rare. But they seem to have had a specific niche - smaller swivel guns etc. intended for anti-personnel uses, the larger ones I don't see too much after the 16th Century. I am pretty convinced of the ubiquity of breach-loaders into the 17th and 18th centuries because I often excitedly saw one somewhere at a castle or in a museum hoping it was a medieval one only to be disappointed by the little plaque which said it was comparatively recent.

Naval warfare in the 17th Century of course was dominated by large quantities of larger caliber muzzle-loading cannon, but that may have been due to economic and political realities of the time. They had streamlined the process of press-ganing a naval crewman and training them to shoot the muzzle loading gun, the breach-loader may have been more complicated to use ultimately. And again, I think the skill of the labor pool for soldiers was going down.

yes that was part of the general economic shift back toward serfdom too in many places, and part of a generalized inflation which I assume had a lot to do with Peruvian Silver and Canadian furs and Caribbean sugar and indigo, Virginia tobacco and so on. But I'll admit the complexity of the economics of this period are still a bit beyond me. i have tried a few times to figure out accurate comparisons of wages and prices from the 16th Century and came out of it more confused than i started.One of the things you might want to look into is spiraling wage inflation in the 16th century -- it had effects like encouraging the use of slaves as oarsmen, and the decline of stone firing cannons in the west (the stone cannonballs required much more labor to create).

I think the difference is this - the wheellock had a niche, it had a need. You can't really mess about with a match on horseback, I mean you can but it's a major disadvantage. The emergence of the Schwarze Reiter troop type in Northern Europe, and the hybrid adoption of pistols by Polish Hussars, French Gendarmes and others, create this niche for the pistol in cavalry warfare that was effectively exploited by armies and spread from the North to throughout Europe.However, there's a problem with the wheellock analogy. Wheellocks were a new technology at the beginning of the 16th century and they became more prevalent over the 16th century -- not less. Breechloading firearms remained rare, and never established themselves on the battlefield in any capacity (as far as I can tell). They didn't go away, but the technology never established itself. Perhaps they did fall into some sort of economic trap, but given how other technologies continued to develop, it seems unlikely to me.

The breach-loader while innovative and potentially, hadn't been combined with brass or copper cartridges as you noted, or a revolver barrel and a magazine, and wasn't so efficient that you could build up a troop-type around it. Not when it was so cheap to arm 10,000 serfs with basic muzzle loading matchlocks and march them into your neighbor's kingdom.

So I suspect the technology was just stalled until the Industrial Revolution and post French Revolution era spurred a new interest and intensive competition to innovate new weapons systems

GLast edited by Galloglaich; 2017-10-21 at 01:11 AM.

-

2017-10-20, 08:35 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Links to 18th century swivel guns:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/F...ogy_Branch.jpg

http://jamesdjulia.com/item/lot-2339...-cannon-44102/

http://www.bronzecannons.net/81inch_...el_cannon.html

A Dutch example from 1700:

http://www.antiquarianartco.com/item...s/enlargement6

http://nautarch.tamu.edu/CRL/Report10/gun.html

All muzzleloaders.

Links to 16th century and earlier swivel guns:

http://www.lennartviebahn.com/arms_a...ng_swivel.html

http://www.historicalimagebank.com/g...wivel+Gun.html

https://www.the-saleroom.com/en-us/a...d-a44a01157155

All breechloaders.

-

2017-10-20, 08:42 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Don't move the goal posts. In the 17th century breechloaders were very common, in the 18th century . . . I still can't find an example of one (i.e. a European one) -- other than the one you posted. I believe there are more, I just can't find them. My suspicion is that the trend toward fewer breechloaders and more muzzleloading swivel pieces began around the middle of the 17th century.

Last edited by fusilier; 2017-10-20 at 08:49 PM.

-

2017-10-21, 01:11 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Jeez man, seriously? How much unpaid research you expect me to do for his forum thread? I don't know but you can easily find a lot of breach-loaders from the 17th Century (which I guess you just conceded) and the 19th Century with google image search. or maybe they used some different technical name in the 18th Century, I'm not going to spend hours trying different search terms for specifically 18th Century stuff. it might require a specific search term like a term of art they used in French or Portuguese or something.

Or who knows, maybe for exactly 100 years they shifted exclusively to muzzle loaders and then went back to breech loaders again. I really have no idea. I can tell you that you see these things all the time in museums and fortresses, can't say how many were 1700's vs. 1800's or 1600's though it's not the type of thing I cared about.

here are some 19th Century ones.

Spoiler: 19th Century Breach-loading swivel guns

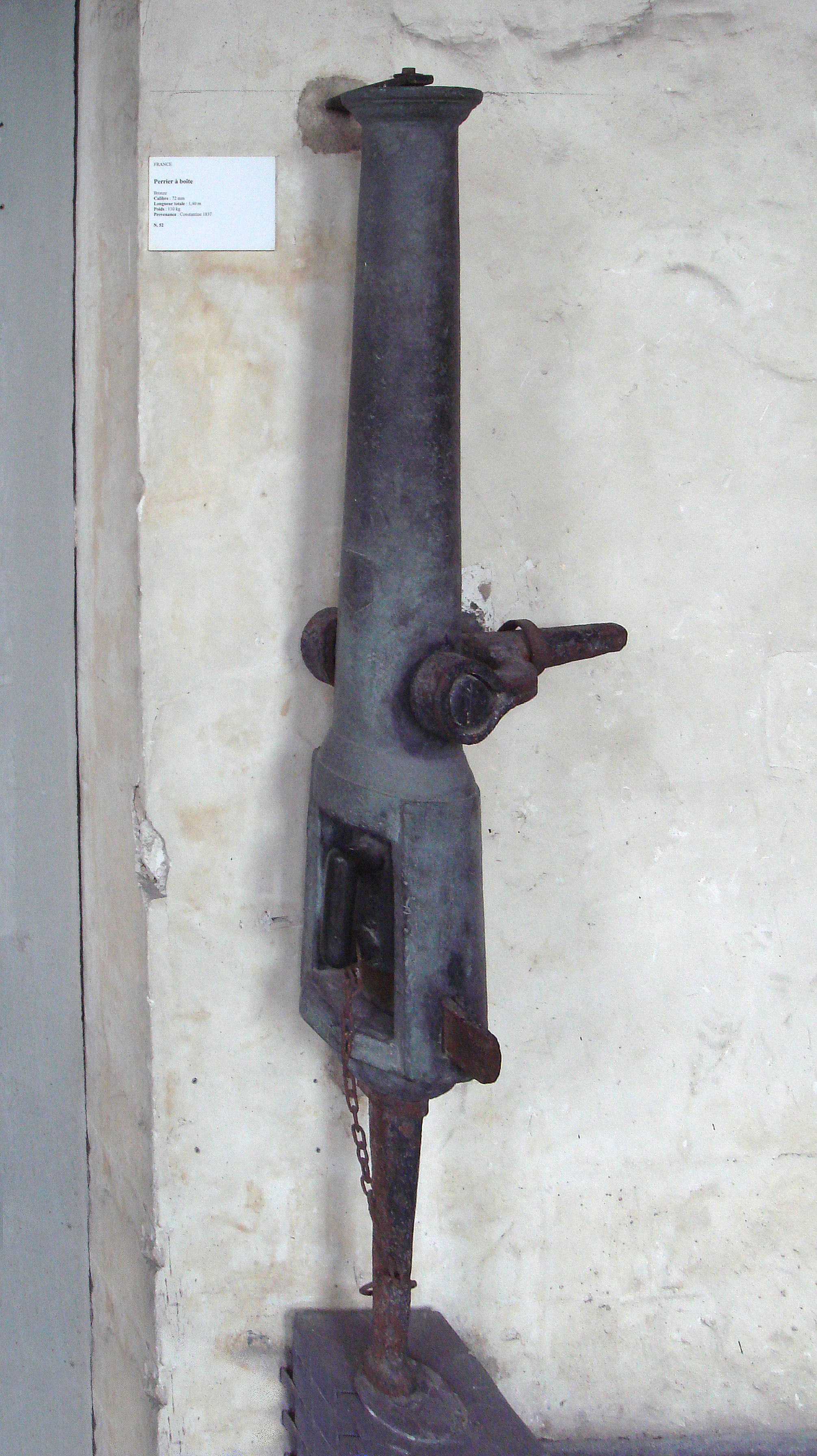

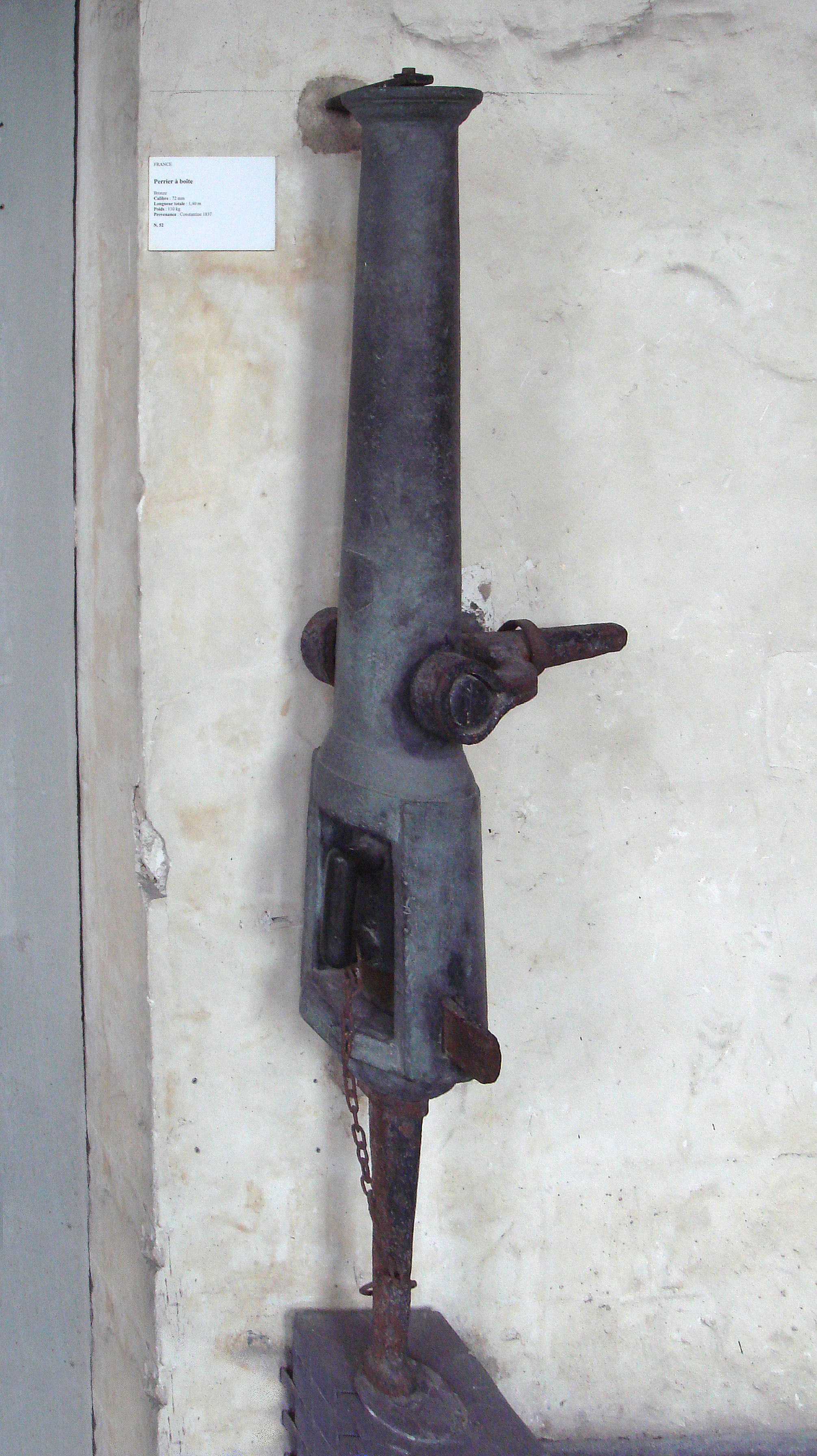

French 1837 72mm caliber

American rifled breach loader 1890

Last edited by Galloglaich; 2017-10-21 at 01:16 AM.

-

2017-10-21, 01:58 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2008

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

I never questioned that they were used in the 17th century. I questioned the 18th century use. You showed me *one* example from that time period. I pointed out that the vast majority from then were muzzle-loading.

I'm not asking you to do unpaid research. I'm pointing out that what your claiming, doesn't square with the research I've done. I'm sorry if that offends you.here are some 19th Century ones.

Spoiler: 19th Century Breach-loading swivel guns

French 1837 72mm caliber

American rifled breach loader 1890

The top image is of an 1859 Belgian piece. Along with the 1890s breechloader they belong to time when new breechloading artillery was being developed, which does not have a direct link with medieval/renaissance designs.

That 1837 French breechloader you mentioned -- you should read the caption on wikipedia. If you had you might have noticed it read:

". . . seized by France in Constantine in 1837" -- not made in France. I admit I don't know when it was made, or where it was made. But that's no reason to misattribute it.

This is getting stupid. I don't have the time to vet every single image you post, and correct the misunderstandings that you've applied to them.

-

2017-10-21, 07:41 AM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jul 2016

- Location

- Earth

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Could catapults be tactically and strategically effective after the onset of the cannon? It seems to me that things like trebuchets could provide a cheaper and safer form of advanced fire, and could be quickly assembled on the spot rather than dragged into position. Furthermore, you can use them to lob things besides large rocks, such as dead cows to spread disease and human heads to demoralize the enemy. So, even if it didn't happen IRL, could such siege instruments be effective into the Renaissance?

-

2017-10-21, 08:58 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2010

- Location

- Beyond the Ninth Wave

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Originally Posted by KKL

Originally Posted by KKL

-

2017-10-21, 09:34 AM (ISO 8601)Firbolg in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Also:

1. Different education of specialists. Education costs money. So you try to go for the one that will give better value to your money.

2. Once fortresses were built with cannons in mind, I doubt that older throwing machines could have achieved much. Originally Posted by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1955

Originally Posted by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1955

-

2017-10-21, 11:33 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jul 2013

- Location

- Dixie

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Actually, as cannon became both more prevalent and more powerful, fortress walls became thicker but shorter--cannon could shoot through walls that would resist trebuchet/catapult projectiles, but couldn't really do indirect fire, so fortresses didn't need high walls to defend against lobbed projectiles. A catapult probably -could- do some damage to a fort built to resist cannon, but by that point the cannon will be much more damaging. I'm not entirely sure why people didn't try and revive catapults to bypass fortress walls, but I imagine it has to do with the greater versatility and power of cannon, coupled with the specialist education required to build and crew them that you mentioned.

I'm playing Ironsworn, an RPG that you can run solo - and I'm putting the campaign up on GitP!

Most recent update: Chapter 6: Devastation

-----

A worldbuilding project, still work in progress: Reign of the Corven

Most recent update: another look at magic traditions!

-

2017-10-21, 11:54 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2007

- Location

- Bristol, UK

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Wushu Open Reloaded

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Wushu Open Reloaded

Actual Play: The Shadow of the Sun (Acrozatarim's WFRP campaign) as Pawel Hals and Mass: the Effecting - Transcendence as Russell Ortiz.

Now running: Tyche's Favourites, a historical ACKS campaign set around Massalia 300BC.

In Sanity We Trust Productions - our podcasting site where you can hear our dulcet tones, updated almost every week.

-

2017-10-21, 12:17 PM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jan 2012

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Besides the issues mentioned by others before me, trebuchets were probably also vulnerable to counter-fire coming from the fortress.

EDIT: I suppose in theory you can load rotten carcasses into a shell and shoot them over using a mortar too, although I doubt if anyone had really done this.Last edited by wolflance; 2017-10-21 at 12:43 PM.

-

2017-10-21, 12:33 PM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2016

- Location

- The Lakes

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

A trebuchet is also not something you just roll up with, is it?

It is one thing to suspend your disbelief. It is another thing entirely to hang it by the neck until dead.

Verisimilitude -- n, the appearance or semblance of truth, likelihood, or probability.

The concern is not realism in speculative fiction, but rather the sense that a setting or story could be real, fostered by internal consistency and coherence.

The Worldbuilding Forum -- where realities are born.

-

2017-10-21, 01:07 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2010

- Location

- Beyond the Ninth Wave

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Originally Posted by KKL

Originally Posted by KKL

-

2017-10-21, 01:43 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jul 2013

- Location

- Dixie

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

I'm playing Ironsworn, an RPG that you can run solo - and I'm putting the campaign up on GitP!

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

I'm playing Ironsworn, an RPG that you can run solo - and I'm putting the campaign up on GitP!

Most recent update: Chapter 6: Devastation

-----

A worldbuilding project, still work in progress: Reign of the Corven

Most recent update: another look at magic traditions!

-

2017-10-21, 03:37 PM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2017

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

I think this is a key point. Trebuchets are really short ranged compared to cannon. You won't be bombarding the fortress from a hill half a mile away. So anyone setting up their trebuchet to fire dead cows into the fortress, would have to build very substantial field fortifications for it to survive long enough to do it's job. It is probably just not worth it.

-

2017-10-21, 06:41 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

I found one in 5 minutes from the 18th century which was a breach-loader and I think you found 5 or 6 others which were muzzle loaders.

Originally, upthread you said that breechloading guns were phased out after the 16th century, then two posts later you concede (apparently after some googling) that they were still very common in the 17th (and accuse me of "moving goalposts"!). And we know there were tons in the 19th when they started developing new innovations for that type of gun again. So suddenly the whole discussion, now inevitably a debate - hinges on finding more examples of this specific type of gun from the 18th Century.

That, to me is a little bit ridiculous. And no, despite being tempted I'm not going to spend a ton of time running down more images because I already posted a perfectly good one, and finding a few more won't prove any point about how common the actually were, whether they were effective to begin with (I think they clearly were and I don't believe that is an outlier position but I'm not prepared to prove that here aside from posting videos) or whether muzzle-loaders were somehow technically superior.

If you want to find out anything like that you'll have to find some academic studies probably.

I fail to see whether that specific gun being captured by the French in 1837 or made by them in 1837 really changes anything about the argument...? What about the 1717 gun? Did Da Vinci make a time machine and put a 15th Century one on that shipwreck in Honduras ? (and actually if I remember right the article mentioned that there were two of those guns found on that same wreck).I'm not asking you to do unpaid research. ...

This is getting stupid. I don't have the time to vet every single image you post, and correct the misunderstandings that you've applied to them.

But what this is devolving into is some kind of (predictably) bitter debate about what you can find with a google image search in 5 minutes. Anything beyond that would mean getting real sources.

I already have a whole lot of real sources available for Central Europe in the Late Medieval period so I'm ready to go on a deep dive for that time and place whenever somebody wants to. It took me close to 15 years to get all that data together but I have it at my fingertips now so to speak.

But getting that deep for some other era would require real research, not reading 1 or 2 books or doing a few google searches, and I'm not prepared to go there to win some unwinnable internet debate. Specifically your best bet for images would be to pick up a bunch of auction catalogues and pour through them but that could take a long time. You'd still need some kind of study or something to establish any meaningful pattern.

I hope folks enjoyed the NOVA documentary and the videos of the breech-loading cannons being fired at targets and learned something from them, I personally find that kind of thing informative. beyond that I guess signal to noise ratio starts to plummet inevitably.

G

-

2017-10-21, 08:00 PM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2016

- Location

- The Lakes

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

It is one thing to suspend your disbelief. It is another thing entirely to hang it by the neck until dead.

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

It is one thing to suspend your disbelief. It is another thing entirely to hang it by the neck until dead.

Verisimilitude -- n, the appearance or semblance of truth, likelihood, or probability.

The concern is not realism in speculative fiction, but rather the sense that a setting or story could be real, fostered by internal consistency and coherence.

The Worldbuilding Forum -- where realities are born.

-

2017-10-22, 02:03 AM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Apr 2013

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

I check this thread every day for updates, it consistently provides some of the most interesting commentary I know of. There are a number of excellent posters who contribute but Galloglaich is a stand out here, which is saying something. I've learned a lot just by lurking and it feels like information that would be difficult and time-consuming to acquire elsewhere.

So yeah, just wanted to throw out a thanks to everyone who contributes and I'm sure I'm not the only person who feels like this.

-

2017-10-22, 09:00 AM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2007

- Location

- Cippa's River Meadow

- Gender

-

2017-10-22, 09:07 AM (ISO 8601)Titan in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2016

- Location

- The Lakes

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

It is one thing to suspend your disbelief. It is another thing entirely to hang it by the neck until dead.

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

It is one thing to suspend your disbelief. It is another thing entirely to hang it by the neck until dead.

Verisimilitude -- n, the appearance or semblance of truth, likelihood, or probability.

The concern is not realism in speculative fiction, but rather the sense that a setting or story could be real, fostered by internal consistency and coherence.

The Worldbuilding Forum -- where realities are born.

-

2017-10-22, 09:16 AM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jan 2012

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

OK now I got a new question. It's about the whole concept of knighthood. I found it extremely confusing.

From what I read, knights basically started out as relatively wealthy professional soldiers that could afford horses (among other equipment), then evolved into a landed warrior class of their own that were given lands in exchange of feudal obligation to their lords, then became a type of minor noble themselves, sitting at more-or-less the lowest hierarchy of the aristocratic ladder.

Then things start to get confusing (for me). From what I understand, knighthood was the lowest level of nobility, thus logically there must be nobles of higher rank than knight - for example, a Duke. However, there apparently existed dukes that were not knight, and dukes that were ALSO knight. How does this even work?

And apparently there were some cases that nobles of the highest level - i.e. Francis I of France, a KING (among several other kings), specifically went out of his way to get himself knighted. Wouldn't that be some kind of demotion? Why would he want to do that? How does this "double-title noble" works anyway?

Also, did this also happen to other nobility ranks? i.e. A King decided to...uh, duke himself.Last edited by wolflance; 2017-10-22 at 09:20 AM.

-

2017-10-22, 09:24 AM (ISO 8601)Firbolg in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

I guess catapults would have been harder to build on the fly, what about rolled ropes and humidity problems.

Does anyone know if some master archer has tried shooting an arrow across the rings of the blades of twelve axes struck into wooden supports? Possibly with a composite horn bow? Originally Posted by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1955

Originally Posted by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1955

-

2017-10-22, 10:41 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2010

- Location

- Beyond the Ninth Wave

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

It's a question of time and place. Take knighthood in the modern UK, which is granted as a sort of "royal seal of achievement." It has nothing to do with the fighting profession, or even really the aristocracy. Knighthood tends to start off pretty much as you describe in the vast majority of cultures, but when the aristocracy loses its status as the principal warrior class (for whatever reason), the definition and implications tends to shift.

Take, for instance, Japan, where the arc of knighthood's history is relatively simple.The knightly class began as mercenaries, considered to be vulgar by the aristocracy, but merged with and replaced the ruling class almost entirely over the next several centuries. By the Sengoku period, you had knights parcelling out land to other knights, who were still not a formalized social class - it was only when the peasant-born Hideyoshi subsequently unified the country, and he closed the gates behind him, that Japan's knights become aristocrats in the conventional sense. And during the relative peace of the Edo period, their status as landowners and warriors waned, and most became little more than middle-class bureaucrats with a sword license. Eventually, due to foreign pressures, vestiges of the old warrior culture reappeared, removing the knightly Tokugawa dynasty from power and reinstating the last vestige of the pre-knightly aristocracy, the Emperor. Not long after, he abolished the class altogether, although much of it went on to form the new economic and political elite.

You should expect knighthood's history to be at least this complex, if not much more so, anywhere you care to look. Remember, knights as a class are an economic and political construct, and will change as the economics and politics of their class change. Originally Posted by KKL

Originally Posted by KKL

-

2017-10-22, 11:33 AM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jul 2016

- Location

- Earth

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Knight was, as you said, the lowest rank of nobility, but it also meant much more than that. A knight was, from the origin, a defender of a certain lord, place, nation, or church. So, a King or upper noble would often be knighted to join certain orders, such as the Crusader Orders, the Knights of the Bath, Knights of the Golden Fleece, etc. Knighthood, furthermore, even for upper-ranking nobles, was conceived of something that had to be earned--while merely being born to a Duke would make you the heir of the duchy, you still had to train or otherwise distinguish yourself to become a knight. Finally, knighthood--particularly in national orders--could be used by kings (esp. in the late medieval period) to distinguish their subjects without handing over control of a valuable fiefdom.

As a noble, you could generally hold multiple titles, and would be addressed as the highest ranking title when brevity was required, save that for someone who was both an Emperor and King the titles would 'stack' to "Your Imperial & Royal Highness". Therefore, Charles V would be "His/Your Imperial & Royal Highness" when brevity was required or preferable, but in full held the title:

Spoiler: Charles V's full list of titlesHis Imperial and Royal Highness Charles, by the grace of God, Holy Roman Emperor, forever August, King of Germany, King of Italy, King of all Spains, of Castile, Aragon, León, of Hungary, of Dalmatia, of Croatia, Navarra, Grenada, Toledo, Valencia, Galicia, Majorca, Sevilla, Cordova, Murcia, Jaén, Algarves, Algeciras, Gibraltar, the Canary Islands, King of Two Sicilies, of Sardinia, Corsica, King of Jerusalem, King of the Western and Eastern Indies, of the Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Brabant, Lorraine, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Limburg, Luxembourg, Gelderland, Neopatria, Württemberg, Landgrave of Alsace, Prince of Swabia, Asturia and Catalonia, Count of Flanders, Habsburg, Tyrol, Gorizia, Barcelona, Artois, Burgundy Palatine, Hainaut, Holland, Seeland, Ferrette, Kyburg, Namur, Roussillon, Cerdagne, Drenthe, Zutphen, Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire, Burgau, Oristano and Gociano, Lord of Frisia, the Wendish March, Pordenone, Biscay, Molin, Salins, Tripoli and Mechelen.

Although Charles was a Duke in addition to a King and Emperor, though, addressing him as "Your Grace" would be a major breach of etiquette if nothing else.

Thus, Monarchs awarding themselves lesser titles served to augment their prestige. Furthermore, if they had a legitimate claim to the territory but did not currently rule it, this essentially gave them a justification for opposing their rule. Furthermore, if they already controlled a territory, it prevented their subjects with their own claims to the title from claiming control--one couldn't, for example, both be a loyal servant of Henry VIII and claim the title Duke of York, even if they were a descendant of the powerful House of York. Likewise, the Tudor Monarch's holding the title Lord of Ireland forestalled the Gaelic lords from claiming the title High King of Ireland without risking a war they couldn't afford.

And, finally, secondary titles might be acquired almost by chance--as a side effect of a marriage into a different family, or the death of a distant relative without heirs and their subsequent decision to have you, a powerful king, appointed as their lord and protector.

In no instance where a noble or monarch held a lesser title was that title taken as a "demotion", though a king who listed some unimportant barony in their title might risk coming across as petty.Last edited by KarlMarx; 2017-10-22 at 11:35 AM.

-

2017-10-22, 11:44 AM (ISO 8601)Firbolg in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Knighthood wasn't just a rank. Most nobles were knights. Emperor Barbarossa made a huge feast for the investiture of his sons to knights, and had huge numbers of nobles invited. These were all of different ranks, but were united by the fact that they all were knights, the Emperor too.

In general, knight sure is a concept with many different meanings. The attempt to work cross-language doesn't exactly help. What is occasionally called knights for antiquity are classes distinguished by their money (Athenian hippeis, Roman equites). Then we start having buccellarii, which you can search yourself, because I am not exactly sure of what they did. There is the Constantinian reform of border defense, with larger cavalry squadrons. There is the ideal knight starting out with the historical St Martin and St George. At some point, the Latin word to refer to this idealizes knight becomes miles, which earlier simply meant soldier (see Erasmus's Enchiridion Militis Christiani). Once again, we have a military evolution with barbarians entering the scene with efficient cavalry forces.

Then we have Charlemagne with his paladins. I think we have Heberard's testament, which describes him as a great feudal lord who fought as heavy cavalry (there are descriptions of the weapons he leaves).

However, to develop the knight to a ideal figure, I believe we need to wait for courtly culture. So we have a Mediterranean ideal of the knightly honour, among the Arabs too, although I don't remember the name they gave it. We have the ancient images of the brave (St George) and the charitable (St Martin) knights, mixed with the crusaders, so also ideas of pilgrimage, and of course the new knightly orders, while you have a common ideal of courtly love and adventure which take directions opposite to standard morality. So when the nobles called themselves knights, they were referring to a rather composite and complex concept, that I find very hard to explain succinctly. Anyway, this is why even a king wanted to be a knight.

This had some effects even in republics. So Dante for example served in a branch of the Florentine cavalry that was called feditori, and were lightly equipped and expected to be the first to hit the enemy. As a result, they were overcrowded by nobles, because of the great honour that was bound with the danger. This had more to do with the concept of the right occupation for a nobleman. Some later development got slightly weird, so, apparently, the people of Florence assumed the authority to knight meritorious citizens. Originally Posted by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1955

Originally Posted by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1955

-

2017-10-22, 02:50 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

yes, knighthood is a very complex thing in most parts of the world. It took me a long time to get a basic grip on the idea. It's surprising how little this is generally understood in our culture given the huge importance placed on the concept.

I think I have a grip on it now though and I can break down what it meant in Latinized medieval Europe in three eras.

I'll get into the background a bit since it's Sunday and i have the time, but for those in a rush to get to the basic concepts of knighthood you can skip ahead to the High Medieval Period.

Late Merovingian / Carolingian period

in the Migration era, most of the male members of a Germanic, Gallic, Slavic, Nordic or what have you tribe, and apparently some of the females too, were warriors. There was distinctions between greater and lesser families (what we call today nobles and commoners) and of course slaves, but there was no distinct formal knightly class per se, and boundaries between noble and commoner were pretty fluid and amorphous too.

The rise of Franks as the Merovingian and then Carolingian dynasties consolidated power in Europe, also coincided with a number of increasingly dire threats to the emerging Latinized European Order. The Vikings of course were invading from the North and up the rivers along the coasts, the Moors and Saracens were invading from the South and conquered Sicily from the Byzantines and the Iberian peninsula from the Visigoths, and the Huns and later the Magyars were encroaching into German lands from the East. The Franks and other major rulers were scrambling to put in place a defensive system which could handle the increasing onslaught, and they found that the tribal armies were often incapable of handling the incursions - specifically lacking suitable equipment and troop types. The migration era can be seen as a time where a lot of the Europeans themselves were kind of like refugees - they had been roaming around for generations, and this resulted in a certain amount of poverty and probably a decline in some capabilities, making it harder to handle the huge, well organized armies of invaders seeking to ravage the land and enslave the population. It was a dangerous time.

The troop type which the Frankish elite found the most effective at this time (say 8th - 10th Centuries) was heavy infantry (armored with mail) and heavy cavalry (armored with mail, on a horse and armed with a lance) and also archers. But the cavalry was the most useful if only because they could reach trouble-spots more quickly, and the most expensive to equip for these poor tribes and the authorities wanted more and more of them. To ensure that they got the troops they needed, they started writing special laws, which we call Capitularies. This, along with Church records, is the source of most of what we know about the formation of the early Feudal System in Latinized Europe.

Carolingian and Merovingian Capitularies, and their rough equivalents like the Norse Leidang stipulated conscription rules for tribal militia so that for example, for every five men, they had to equip one archer, and for every ten men, one horseman, and for every twenty men, an armored horseman. And so on. Some of these get into detail about the equipment which can be interesting. As the tribes were poor (the Saracen, Vikings and Magyar raiding wasn't helping with this) and the Frankish authorities had an increasing need for more and better soldiers but with very limited administrative resources. They needed to take things further.

The Dawn of Feudalism

In the late Carolingian period, during and after the reign of Charlemange himself, you started to see a new innovation. Some of those 1 in 20 or 1 in 10 guys who were meant to be the fighters equipped by the others, started to be granted land of their own by the Kings and their noble vassals (mainly the counts - using the latin term Comes, and the Abbotts and Bishops). They were then given the right to force the others to supply them what they needed so that they could show up to muster appropriately armed with horse, armor, (eventually horse armor too though it's unclear precisely when that started) and increasingly, some attendants and vassals of their own.

This did not precisely correlate with nobility, it's worth noting. But it did overlap.

Conversely the Carolingians started dusting off old late Roman laws as justification to force the other pepole, the 19 out of 20 whose work had to equip the armored rider, so that they were not allowed to leave their land. This represented the onset of medieval serfdom, a Roman concept left over from the large farming estates in the Mediterranean called Latifundia. That has a whole rather sinister history of it's own but it's another story for another time. In general, the establishment of Feudalism was incomplete at best and had a lot of problems. Many of the new landed gentry were harsh or incompetent administrators, and many of their families formed rivalries with each other and began spending as much time fighting among themselves as dealing with any external threats. Many of the tribes, accustomed to freedom, resisted being turned into serfs, often successfully. Only certain areas became what we think of as the typical "lord in the manner / serfs in the field" type of Feudalism, others especially in mountainous, marshy or heavily forested areas retained their freedom but made different types of arrangements with their Frankish rulers and ultimately did play ball in some way or another as far as providing troops to the New Roman / Frankish Empire. There was a lot of internal strife though with petty warlords increasingly fighting each other and nominal "peasants" remaining restive and often going on the warpath themselves. Latin Europe became safer from foreign invasions but a new kind of permanent internal struggle came into being.

The Feudal system, as rough and harsh as it was, did work and the emerging professional warrior caste proved capable of checking the Vikings, routing the Magyars and gradually pushing back the Moors. And if the slave raids never really ended in the Southern coastlines, at least they were no longer so disruptive as to throw entire provinces into turmoil. In addition, the subtle but ultimately substantive innovations they brought to the old Sarmatian concepts of heavy Cavalry proved so effective in the field that it allowed the Latinized Frankish forces to launch their own Crusades in the Middle East and for the Normans to capture Sicily and Naples for themselves. In some legal documents the emerging professional cavalry caste was starting to be (very roughly) equated with the old Roman Equites, the equestrian rank which became associated with knighthood though it's not precisely the same thing. Arguably the peace established by the knights helped make possible the rise of the new emerging urban economy.

The High Medieval Period.

The period roughly 11th through the 13th Century saw major economic and social changes in Europe. The Empire broke up into three major zones - France in the West, Germany (the Holy Roman Empire) in the East, a series of smaller states in the Center roughly down the line of the Rhine through the Alps and into Italy. The Commune movement spread throughout Italy, Flanders, parts of France and Spain, and Southern Germany and Bohemia. Peasants banned together for mutual protection and created or began to revive fortified urban centers for mutual protection. These in turn spawned markets.

The nobility and the military class, now also commonly called miles milites an old Roman term for soldier, or more simply miles (in German speaking areas they were also called Ritter for 'rider") almost universally built fortified homes which we now call castles. Most of the original ones were wooden or made of half timber / wattle and daub construction. Stone castles came into being gradually as the internal competition between warlords heated up. The knights of this era overlapped with the nobility, but it was a distinct rank. In order to do their jobs as soldiers, the knights were given special legal rights. They wore a special belt and gilded spurs. They were allowed to go everywhere armed. Their word carried legal weight in court (literally - the court of nobleman, or in the court of a tribal, town or religious magistrate). And they granted each other an emerging culture of professional courtesy on the battlefield, which meant in effect, that if captured they would be ransomed back to their overlord or to their family rather than being killed. This was a particularly nice perk to have needless to say. Nobles were not automatically knights, someone would usually be made a knight after they had proven themselves in battle. Even powerful princes had to follow this rule to some extent and would not be made a knight until they had actually seen combat.

Importantly, knighthood was not restricted to the aristocratic estate by any means. Burghers could become knights, monks could be come knights (usually as part of the special fighting religious Orders like the Knights Templar, the Knights of St. John of the Hospital, the Sword Brothers and the Teutonic Knights, as well as dozens of smaller knightly Orders found especially in frontier areas like in Spain). And even peasants could be made knights. The knights themselves sometimes united politically and militarily and formed a rivalry to the old nobility or the Church. They threatened commerce and the towns by kidnapping merchants on the roads and on the seas, forming a new concept, the Robber Knight. They also continued to fight among each other to gain more and more territory. Some of them who had humble origins became rich and married into the nobility as they gained land. Once some king or princes granted them land and made them a vassal, they moved up in status regardless.

Ministerials

A very curious thing happened in this era in the history of knights. As the rivalry between the nobility and the armed knightly caste got more and more intense and dangerous, Higher ranked nobility, or larger property owners such as Towns, Abbeys, wealthy merchants and so on, in order to have more muscle to face their enemies, began to arm and equip their serfs. I know the details of this a bit in the German speaking areas but there was similar things done in England and many other places. In some parts of Europe the term 'sergeant' means something similar - a knight who is equipped by a Lord - he doesn't own his horse and his armor himself, but fights for another. Confusingly, the term 'men at arms' or gens d'arms in French sometimes refers to an unfree knight like a Ministerial, but sometimes refers to a noble knight or just any kind of cavalry. Depending widely on the context. Personally I find that an unreliable term unless you are talking about a relatively short span of time (10 or 20 years) in a specific area.

Nevertheless, these 'serf knights', known as (latin) ministerialisor (German) Dienstmann in German speaking lands, were conferred most or all of the respect of the knightly caste. The special rights of knigthhood seemed to be deemed necessary for them to do their job properly. There were also special administrators and effectively, courtiers recruited from this same class. Ministerialis had some advantages over noble knights or other free knights, as the latter could be unruly and often exploited the immunity provided by armor, a fast horse, and a fortified home to make their own minds up as to whether or not to support their Lord in a given conflict, while the ministerials were more loyal to their Lord and usually more disciplined. In a curious repetition of the previous cycle with the original miles, Lords (who could be a Count or a Duke, or could just be a Town or an Abbey) began to grant control (as opposed to ownership) of land to their ministerials so as to allow the latter to equip themselves for battle and meet their other needs.

Free Imperial Knights

Another odd nuance of the knightly caste, is that not all of them were Vassals to a lord. Many remained independent. Some of these became mercenaries or mercenary contractors (famously called Condottiere, literally Contractor, in Italy, often referred to simply as 'Captain' in many other areas). In the German-speaking areas, they were called 'Knights of the Empire' or Reichsritter, or in Latin, Eques imperii). In English we call them Free Imperial Knights. Many of these men (and some women) were from the old tribes or clans who had traditionally never had their status downgraded into serfdom. Over time this became a rank of nobility which in German-speaking areas was called Edelfrei. In theory these people and their families owed fealty to the Emperor, but this was seldom invoked, particularly after the major interregnums of the 13th Century. In Poland you had the Szlatcha who were basically free and armed tribesmen - some would say peasants, who remained armed and over time extracted concessions from various Kings and princes and gained the status of nobility and often knighthood, even though many of them were very poor and owned little or no land.

SIDEBAR - I know all this is complicated a bit confusing but you can think of it on a system-wide scale as simply a kind of Roman or Middle Eastern style hierarchy (Feudalism) unevenly imposed over a Barbarian (Germanic, Gallic, Slavic, Nordic etc.) clan or tribal society. Both systems existed simultaneously and neither one ever really had total control. In addition you had the Church and an emerging urban system which played by it's own rules. All four tried to impose their own reality on the others, with varying degrees of success and one ascendant and another declining in any given part of Europe at any given time. These four systems and the perpetually uneven balance between them are basically what defined the middle ages as such.

Over time the Ministerials and the Free Imperial Knights began to merge as Ministerials sought out Reichsritter status as the key to personal freedom.

The Lance

At this time, a true knight was not just one rider on a horse - he was the leader of a small unit called a Lance of anywhere from 3 to 10 or even 20 riders (this varied widely by specific time and place, and whether they were self-organized or organized by some King or Prince). Typically, by this time (I think somewhere in the 13th Century) the knight himself would be armored and his warhorse(s) would be armored too. He would go into the field with 2 -4 horses, including both warhorses like chargers (destrier or palfrey) and riding horses like amblers or coursers for traveling or scouting. In addition, he'd be accompanied by at least one or two lancers (armored warriors on an unarmored horse) and increasingly, at least one mounted crossbowmen or mounted archer (depending on when and where specifically) and often 1 or 2 lightly armed or unarmed attendants or 'valetti'. Sometimes they would also have something like Dragoons - mounted men who were expected to fight as infantry. The lancers might sometimes be 'squires', something like a journeymen knight, and the valets might sometimes be pages, a kind of apprentice knight. However this was not always the case.

In Germany you also had the curious tradition of the Trabant, the 'satelite', armed men who fought as infantry and who accompanied the knight on foot. The main significance of these guys to me is that they sometimes organized Fechtschuler and were therefore associated with the Kunst Des Fechten, or the fencing / martial arts systems of Central Europe. Too much to get into in this already long post though.

Spoiler: Knight and Trabant

Knight and Trabant famous Durer painting

This is important to point out because it became a big deal later on. Sometimes a young noble would be put into the care of a trusted knight who would help him gain battlefield experience and as soon as possible, knighthood, hopefully without getting killed. The lancers were sometimes 'part time knights' - often burghers or sometims free pesants or common gentry (Yeomen is an English term which sort of fits here), who were sent to join a princely or Royal army by a town, and had sufficient equipment and skill to fight as a lancer. These men would also expect to be knighted or given the squire rank, which eventually came to mean roughly the same thing as a knight though more on that in a minute.

Lances were further organized into banners which were usually led by nobles called 'Bannerets'. Sometimes these fellows weren't nobles either though.

Late Medieval Period

Ok whelp, I'm out of time now ... this took too long even for a Sunday. But lets just quickly summarize some of the big changes of this era.

As most are aware, infantry militias started to defeat noble armies dominated by knights in the late 13th and early 14th Centuries. In the High Middle Ages towns started evicting nobles from the towns and also began increasingly knighting their own citizens. Merchants, craft guild aldermen, and elite 'Patricians' actively participated in the tournament circuit, sometimes dominating it, prompting princes to start organizing special "Nobles only" tournaments. The rivalry between the urban estate and the knights, especially when they became robber knights or raubritter, accelerated, with the towns struggling to keep the roads open for commerce and their merchants safe, and the knights often suffering as towns deployed cannon to knock down their castle walls and hanging them in reprisals.

Ultimately both towns and knights ended up having trouble with the Princes in the Early Modern era.

The four powers of medieval Europe led to many difficulties, one of which was that having status in one domain (say a town or a princely court) didn't necessarily give you status in the other. So nobles cautiously sought out citizenship with towns, so that they would have some town rights but tried to negotiate so as not to be under too many legal, financial or military obligations to the town; conversely, townsfolk sought out the status of knighthood - again trying to do so without conferring too many obligations either from their own towns taxes or militia requirements or to regional princes.

The bare minimum level of this was an 'Esquire' - technically a squire but it effectively meant knighthood, conferring all the same rights in the princely court and within the Church domains. Many burghers and some more formidable peasants acquired knightly coats of arms through their status of knighthood, often specifically of the Esquire rank. Kings and princes also granted this status to their functionaries like tax collectors and magistrates so that they could go about their business without running into problems with their legal status. The coats of arms of commoners were distinguished by the type of helmet on the crest. Artisans had a closed jousting helmet, patricians had one with bars, if I remember correctly.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgher_arms

This is further confused when, having ended the independence of their cities, the French King determined he needed the urban elite to have sufficient rights to do business without interference in the princely courts so he (I think Louis XIV though i could have this wrong) gave all the higher ranked burghers in the major cities like Paris technical knightly status, effectively making them petty nobles. This, i think, is the origin of the snootier more elitist connotations of the word Boureois as opposed to Burgher. In the middle ages they both meant the same thing - just town dweller.

The association with magistrates, lawyers and wealthy burghers is why some people today especially Attourneys put 'esquire' on their business card. I think.

TL : DR Knight was not the same as nobility, though many were and knights and nobles overlapped. Most nobles became knights. Some knights were actually 'unfree' serfs, some were burghers, some were robbers, and some were monks.Last edited by Galloglaich; 2017-10-22 at 03:08 PM.

-

2017-10-22, 04:22 PM (ISO 8601)Dwarf in the Playground

- Join Date

- Sep 2017

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Ok, I know this has been asked in earlier incarnations of the thread, but I am struggling to find them in the search function of this website, and don't fancy looking back through a thousand pages of thread.

How much did items cost in the late medieval period? In particular weapons and armour. Preferably with sources if people have them to hand. I am under the impression that the majority of people were able to afford a sword in this period, including peasants, and that many of them could afford good armour too- I have read this in earlier versions of this thread I now cannot find I have said as much in a conversation, and now am being asked to back this up (after all, it does oppose the common perception of late medieval life). This time, I will make sure to save the sources.

I have said as much in a conversation, and now am being asked to back this up (after all, it does oppose the common perception of late medieval life). This time, I will make sure to save the sources.

I recognise prices in the middle ages are a loose thing, and comparing prices is tricky with all the different currencies, and different levels of debasement.

-

2017-10-22, 06:03 PM (ISO 8601)Firbolg in the Playground

- Join Date

- Nov 2009

- Gender

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Re: Got a Real-World Weapon, Armor or Tactics Question? Mk. XXIV

Unluckily, all I could find right now was the price of fish :P

If you are interested, I can post them.

Generally speaking there were books of reckoning and books of shop, in which there are priced items. I remember reading one in which a sword was bought.

I also have how much teaching swordsmen were paid, and the price of taxes in many cities in Europe in 1400, on weapons and other products, although I would need some time to post them, since I would have to do some translation. Originally Posted by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1955

Originally Posted by J.R.R. Tolkien, 1955

-

2017-10-22, 06:58 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Oct 2009

- Gender

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

RSS Feeds:

RSS Feeds: